Innovation from the Corporate garage?

Do you believe that large corporations will drive the next wave of innovation, as presented in the recent Harvard Business Review article “The new corporate garage” by Scott Anthony? I have spent 25 years in the land of corporate innovation and seen all sorts of success and lots of failure. I am confident however that the failures have more to do with execution issues than with the inherent capabilities of corporations to drive innovation and growth.

Do you believe that large corporations will drive the next wave of innovation, as presented in the recent Harvard Business Review article “The new corporate garage” by Scott Anthony? I have spent 25 years in the land of corporate innovation and seen all sorts of success and lots of failure. I am confident however that the failures have more to do with execution issues than with the inherent capabilities of corporations to drive innovation and growth.

Let’s look at the underlying logic: why large organizations should be able to out-innovate smaller ones.

Portfolio management as risk diversification

When looking for underlying logic, corporates do not necessarily have better skills or talent, and it also seems fair to assume they do not have access to superior information and intelligence over small organizations (not anymore nowadays). So, as a consequence, the difference is not in the execution of individual innovation projects.

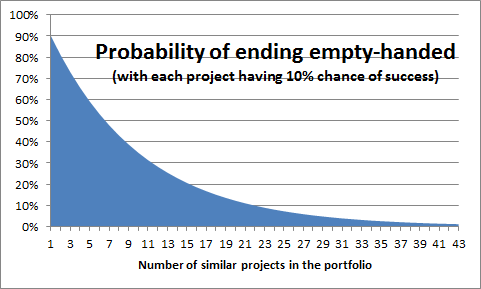

So the key may be to look at the portfolio level. Analyzing a portfolio of disruptive projects, let’s do the math for projects with a 10% chance of success. With just 1 project in the portfolio, this gives us a chance of ending empty-handed (out-of-business) of 90%. But with 40 such projects, that same chance has gone down to less than 1%.

This might still be an oversimplification, since e.g. a venture fund or a shareholder can apply the same portfolio risk hedging across a range of smaller corporations. So what is different in a large organization?

Corporate learning…

What if we could learn across projects, so even a project that is not succeeding can help the others be more succesful? Good innovation management is not just portfolio management: of course, in a well-managed portfolio, stopping projects at the right time is needed. However, the learnings from all such a project can be transferred across the organization. This happens as the people are reassigned on one of the other projects in the same portfolio. It can be more widespread if good project debriefs or post-mortem analyses are implemented. This is the simplest form of synergy in corporate portfolios.

Let’s say what the odds look like if we start with a 10% chance of success for the first project, but every next project has somewhat increased odds due to this learning. The chart below shows the increased resilience in the portfolio due to this synergy (even though every project just has 1% additional chance of succeeding).

This model of portfolio-level risk reduction by sharing learnings across projects is far harder to copy by funds or financial holdings, since it requires links across the projects’ contents (the technologies, the markets, the customer insights, the partnerships, the teams, etc.). The ultimate in portfolio balance along the risk dimension is then to make sure that the underlying activities are organized so that one project’s failure correlates strongly with another project’s success.

An example: in our disruptive portfolio, one set of projects targets the wind energy storage market. The main uncertainty in this case may well be the uptake of wind energy as the main sustainable energy supply. In a future where this will not happen, most likely solar energy will be the winner. So if we can afford to extend our portfolio with projects that target solar energy storage (or transport), our growth is secured. The learning will come from sharing market trends, from common technologies in both domains, and from end-user understanding of adoption drivers for sustainability.

Corporate’s reputation for disruptive innovation

Now, this may not be in line with mainstream thinking and practical experience that a lot of large organizations underperform in disruptive innovation and the associated growth.

Again, looking at this issue from the portfolio angle, the biggest challenge may not be to reduce portfolio risk, but to make sure that the inherent value in disruptive innovations is sustained. The work of Clayton Christensen on disruptive innovation (in the Innovator’s Dilemma) seems to support this view. One way to formulate Christensen’s conclusion is as follows:

- the newness of disruptive options drives underestimation of the value (ignoring low-value disruption)

- the newness of the disruption triggers project risk reduction that reduces the newness but also the value.

Either way, the risk-value trade-off is not properly addressed at the portfolio level. Now, with this reasoning in place why large corporations should be able to out-innovate smaller ones, the main question remains how to organize for succesful execution.